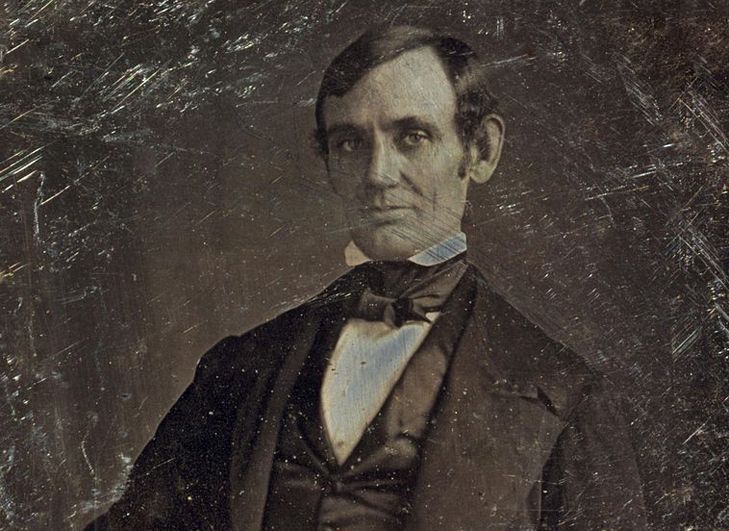

A visitor to Springfield might take some time to stop by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, the Lincoln Home National Historic Site or Lincoln’s Tomb. Lincoln, after all, spent a big part of his adult life in Springfield. He represented the area in the state legislature and in Congress. His children were born there, the only home he ever owned is there, just down the street from his law office and the Capitol building where he gave one of his most famous speeches.

But Lincoln’s Illinois story is far more than just his years in Springfield. The Lincoln family made a long, difficult journey across eastern and central Illinois before the young Lincoln arrived in the city that had just become the state capital. It is a journey with many stops, much failure and sadness. It is also a journey that helped shape the man who would become the greatest President in American history.

Having left Kentucky for Indiana in 1816 when young Abe was only seven, the Lincoln family had uprooted once again and moved farther west just after he turned 21. Lincoln first set foot on Illinois soil in March 1830 nearly 150 miles southeast of Springfield, having crossed the Wabash River into Lawrence County, Illinois. The location believed to be the site where the family first reached Illinois is today marked by the Lincoln Trail Memorial on the bank of the Wabash.

Indiana had brought much grief to young Lincoln: backbreaking labor on his father’s farm and the death of his beloved mother and then his sister.

Lincoln himself had narrowly escaped death at the hands (or hoof) of an angry horse which kicked him in his head and knocked him unconscious for several hours.

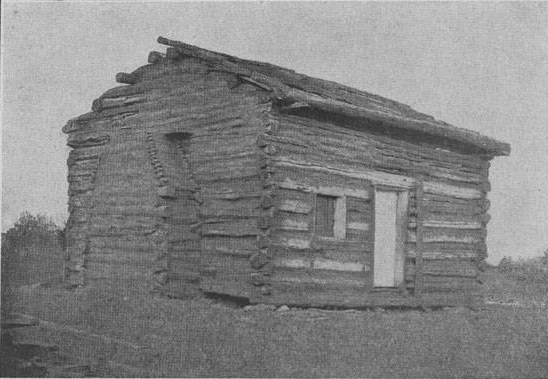

Eager to leave Indiana behind, and encouraged by a cousin who had visited central Illinois, Thomas Lincoln and his three surviving family members took their two wagons across the Wabash and into Illinois, eventually settling on a farm in rural Macon County near present-day Decatur and Harristown.

But the Lincoln family’s luck did not improve. Farming that summer proved difficult, and the winter was especially brutal. When spring finally arrived, Thomas Lincoln decided to move back east, stopping in Coles County where he and Abraham’s stepmother, Sarah, would spend the rest of their days. The 22-year-old Abraham Lincoln heard a different call. He bid his father goodbye and headed west.

Soon thereafter, Lincoln connected with a local flatboat operator named Denton Offutt, who ran his business on the nearby Sangamon River. The Sangamon flowed west from Macon County into the Illinois River north of Beardstown. Offutt needed strong young laborers for his boats, and the unemployed and unattached Lincoln fit the bill.

Visions of a flatboat service running from central Illinois, down the Mississippi to New Orleans soon foundered on a small dam on the Sangamon just northwest of Springfield near the settlement of New Salem. While stuck near the settlement and its mill, Offutt came to the decision to open a general store there with Lincoln as his clerk. This scene is depicted in a painting on the wall of the south wing of the first floor of the Illinois State Capitol.

Over the next six years, Lincoln called New Salem home. During that time he fulfilled many different roles within the community. Clerking in the general store; first for Offutt and then with business partner William Berry; was only a start. It was around this time that one of many stories of the origin of the nickname “Honest Abe” occurred: when Lincoln traveled several miles to return a few cents to a customer he had accidentally overcharged. He also began to develop a reputation as a talented storyteller and earned enough of the respect of his neighbors that he was soon sought out for advice and counsel in legal matters.

But Lincoln’s bad luck continued to plague him. A steamboat venture which he expected to bring prosperity to the area during his first year in New Salem failed. Then Berry died right around the time the general store went under, driving Lincoln into debt. Lincoln fell in love with a neighbor, Ann Rutledge, but she died of typhoid fever in 1835. Here the earned reputation of the dogged, determined Lincoln showed itself yet again as every time he was knocked down, Lincoln got back up and started over again.

In the spring of 1832 when Illinois militia units were called out for the Black Hawk War, Lincoln served with the local company and was chosen as its captain. A man destined for much electoral disappointment over the next couple of decades had just started off with a win. Lincoln saw no combat action in the war, and his service concluded that summer. Ironically, the Army officer who mustered him out of service was Major Robert Anderson, who would command Union forces at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, in April 1861.

Lincoln returned to New Salem, where he threw himself into his first run for the legislature. Winning his hometown by an overwhelming margin, he did poorly elsewhere in the district and failed to capture a seat in the House.

In need of a job, Lincoln found one when the local postmaster position came open. With the less-demanding job of postmaster to a settlement of only a few dozen residents, Lincoln found more time to devote to his voracious appetite for books. He also now had a seemingly unlimited source of material: the many newspapers from near and far which arrived in the New Salem post office. The young man with little formal schooling was becoming one of the best educated men in town.

Not long afterwards, the county surveyor found himself in need of an assistant to do the surveying work in the area around New Salem. Lincoln knew little about surveying, but his reputation as a quick learner and his connections from the militia unit brought his name to the forefront. Soon the self-taught surveyor was settling property disputes and laying out the design of town after town in the countryside northwest of Springfield. He was also making connections that would be invaluable in the fall.

In 1834, Lincoln tried again for a seat in the state legislature, and this time he succeeded. Winning with a platform of working for internal improvements; specifically a better steamboat channel on the Sangamon River to open up commerce to his district; Lincoln set out for the capital at Vandalia. At first, he appeared to be successful. Eager to join the mid-1830s boom in canal building, Illinois had looked at the success of other states to the northeast and began laying the groundwork for a series of canals to open up commerce throughout the state.

The first of these, the Illinois and Michigan canal in northern Illinois would actually break ground and eventually become a reality. Others, however, struggled to make it past the paperwork stage, or failed to collect the necessary bond revenue to start construction. A severe economic downturn in 1837 doomed most of the rest. The Sangamon River was never improved for steamboats, and the expected economic boom did not arrive in New Salem.

Lincoln, however, was a rising star. He had joined together with eight other legislators from the Sangamon County area who, due to their height, were nicknamed the “Long Nine.” They took to the hustings together in 1836 and swept the Whig Party ticket to victory. With the canal plan failing (and momentum being increasingly redirected into the new transportation technology of railroads by an ambitious freshman legislator named Stephen A. Douglas), they now focused on an even bigger prize for their area: they would re-locate the state capital to Springfield.

The need for a new capital city had been growing increasingly apparent for a few years, as the state’s population center shifted farther north. While Vandalia had been centrally-located population-wise in 1820, there was a growing need for a more geographically-centered seat of state government. Someplace like Springfield, for example. Ultimately, in part to help secure votes for moving the capital city, Lincoln would join forces with Douglas and others in an ill-fated system of state funding for canals and railroads that would drive the state deep into debt which took decades to repay.

The year 1836 had held another momentous achievement for Lincoln. The self-taught surveyor had set out to become a self-taught attorney, with some encouragement from the local justice of the peace and other leading citizens of the county. Throwing himself into the effort with the same determination which had characterized so much of his life, Lincoln set to work. Not long afterward, with a testimony to his good character from a local judge and a certification of his qualifications from the Illinois Supreme Court, he achieved his goal of being admitted to the Sangamon County bar.

The failure of the internal improvement effort on the Sangamon River had doomed New Salem. With the town now in decline, and opportunities abounding just a few miles to the south in Springfield, Lincoln set out on yet another move. He opened his law firm in the capital city in 1837, his journey to Springfield now complete.

Next he would set his sights even higher; and would change America forever.